Today we use the word "slum" with a pejorative meaning. In the past, however, it actually only meant the designation of one of the communities grouped around churches that gave their names to the respective slums. From an administrative point of view, the slum was an important division because it located virtually any private request or any public work in the city hall's records.

As the case of our street was special, such clarification was very useful because, without it, today we cannot say whether some archived documents refer to Rotarilor street in the Batiştei and Icoanei slums of Colori de Galben or to the street with the same name in the area Oborului Nou, from the Color of Black.

Over time, the "slums" in the documents began to be referred to as "suburbs" and the "slums" became "citizens". The slums, with churches at their center and not certain streets, had different extents and number of houses and some streets crossed several slums, as was the case with Rotarilur Street. Administratively, the Rotarilor street from the Yellow Color ran through three slums: Oțetari, Batiştei and Icoanei.

The history of Bucharest written by Ionescu Gion includes in its pages the reference to a census from 1798 that shows us the true dimensions of living in these parts of the city. In the areas where the churches were very close, there were also small slums, as was the case with Dintr-o Zi and Enei churches, the first of which had 23 houses and the second 24.

The Batişte neighborhood then had 53 houses and the Oțetalari neighborhood had 54. The Icoanei neighborhood (Ceauş David square) is not mentioned. Around 1848, when a French captain named A. Sabatier was drawing up a report on the Romanian principalities, the slums of Bucharest were still seen by him, an engineer by training, as almost rural places. Its description speaks in the following terms about this organization "[…] the slums, which cover most of its surface (of the capital, N.A.), are made up of real shacks, separated by extensive maidans and not communicating with each other except by roads transformed into dangerous snot in the lightest rain.”

The description was probably also suitable for the Batiste slum, two decades later, when Carol Popp de Szathmari drew a drawing of the church, a drawing reproduced in 1869 in watercolor by Amedeo Preziosi and which is permeated by this very atmosphere. Life in these slums, however, was very attached to community values so that, every time there were subsistence problems for the neediest people, when there were uncertainties about the various properties or when there were community dissatisfactions, the "slums" issued evidence, wrote petitions through through their delegates. We have such documents from the neighborhood, from the Oțetari slum. In 1867, the mayor received a petition from the "notable" of the Oțetari suburb that said:

"[…] By virtue of the right given to me by Your Excellency as notable for all the suburbs of OȘetarii, I make it my duty to inform you that the Street called Rotarul in this suburb is an absolute necessity, as even next spring it will be paved, by which means I think it will be made practicable, because as it is today it is impossible to serve the communication even for pedestrians, I beg you, please order, that the proper preparations be made on the part of the Engineers , for the spring time […]"

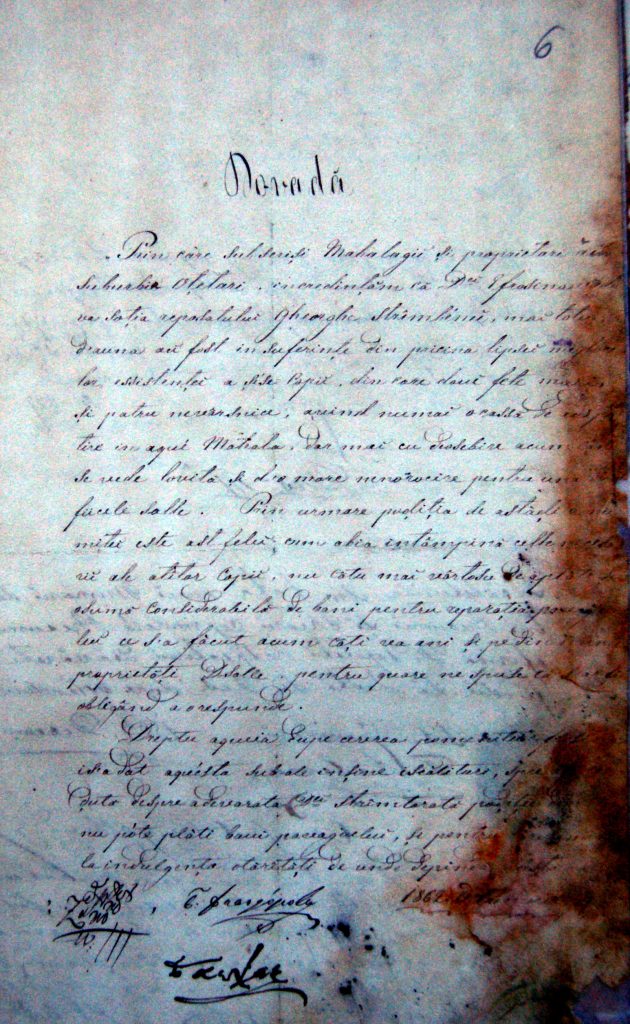

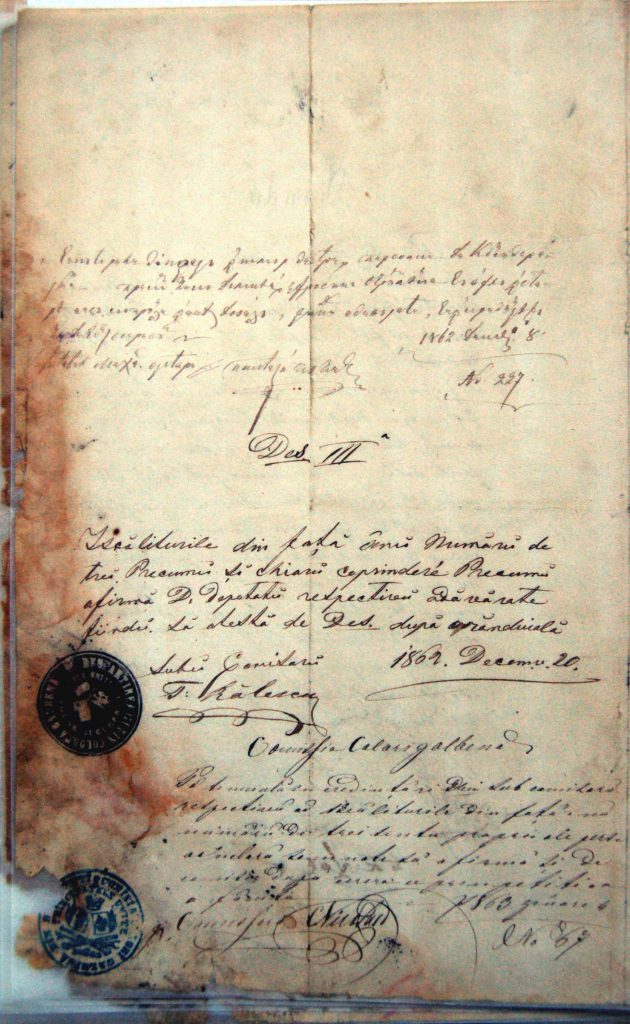

From 1863, also from Oțetari, a document entitled "evidence" has the following text:

"By which the residents and owners in the suburb of Oţetari are subscribed, we entrust that Mrs. Efrosina, the widow, the wife of the late Gheorghe Strîmbénu, has been in suffering due to the lack of means of subsistence for six children, of which two grown-up daughters and four younger ones, having only one cassa (indecipherable) in aqué Mahala, but more especially now for one of her daughters. Therefore, the present-day elevation of the named one is as it barely meets the (indecipherable) cells of so many children, not the more worthy of paying a considerable amount of money for the repair of the pavement that was made [...]"

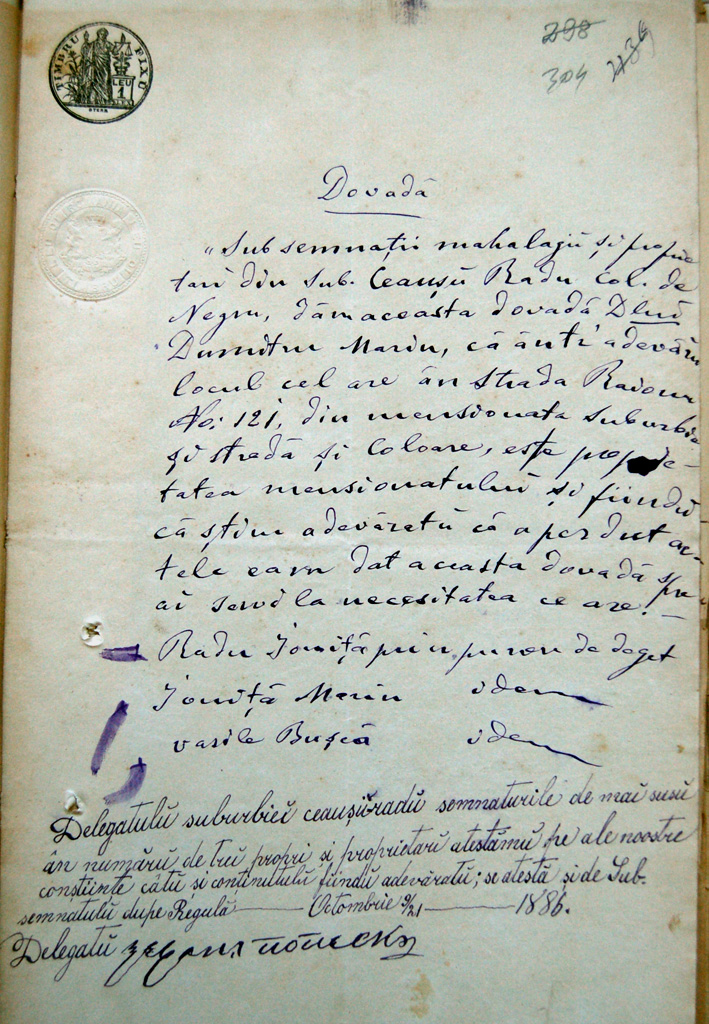

Until late, in 1886, the evidence of the slum dwellers, even being illiterate, was taken into account even when regulating property relations. So we should imagine that somewhere, around the years 1880-1890, such a community atmosphere dominated the place where the house in Caragiale no. 11.